High-speed rail

Is high-speed rail the fast track to transport decarbonisation?

Have high-speed rail networks worldwide delivered on their green commitments? Have they helped reduce carbon emissions in their respective regions, and, ultimately, are such rail systems worth the environmental cost of construction? Julian Turner analyses five of the biggest networks to find out.

T

he International Energy Agency (IEA) reports that rail carries 8% of the world’s passengers and 7% of freight, yet accounts for just 2% of transport energy use, and that high-speed services over long distances constitute an eco-friendly alternative to short-distance air travel by reducing emissions.

However, a study published by the IEA in 2019 entitled ‘The Future of Rail’ reveals that building a high-speed rail network does not automatically translate into significant carbon emissions savings.

To do so, such systems must be energy efficient during construction; trains must be run on clean electricity; the services must be frequent and near capacity; and high-speed rail must entice people out of polluting passenger jets and cars –all while not generating excessive new demand for travel.

Here, Future Rail takes a whistle-stop tour of five of the world’s largest high-speed rail networks to assess if they have delivered on their green commitments and helped to reduce carbon emissions.

China: size matters

China is already home to the world’s most extensive high-speed rail network and, according to the IEA, passenger activity increased by approximately 13% in 2019. Beijing’s 13th Five-Year Plan from 2016–2020 targets a further 30,000km of track aimed at connecting 80% of the country’s big cities.

From an environmental perspective, the key question is whether the train journeys themselves are sufficiently energy efficient – and whether enough passengers use rail or make the modal change from aviation and road travel – to offset emissions produced during construction of the network.

China Dialogue reports that coal consumption, much of it connected with the production of steel and cement, increased for the second successive year in 2018, and CO2 emissions followed suit.

Research shows that operating the Beijing-Shanghai high-speed line, for example, accounts for 70% of its emissions; however, as China adds more renewable energy to the grid, this figure will decrease.

Passengers numbers increased from 2011–14, meaning the per-passenger CO2 footprint fell, and an IEA study shows the Beijing-Shanghai line has shifted people away from flying. However, there is evidence that high-speed rail in China as a whole is under-used; IEA’s study reveals that the number of trains that China runs on its high-speed tracks is almost half that of Europe and Korea.

The extent of the flooding and the scale of the damage is something I have never witnessed before

China is home to the longest high-speed rail network in the world.

The US: a Brightline to low emissions?

Under-use of high-speed rail services is also an objection that has been raised in the US, along with the prohibitive cost of building high-speed infrastructure spanning the country’s vast landscape.

However, as an ancillary to short-haul air travel, US high-speed rail services are already proving their worth. Described as a “private-sector solution to a public need”, Brightline operates a passenger-rail service in south-eastern Florida, and plans to extend its high-speed service to Las Vegas, thus tying it into existing Los Angeles commuter lines and, ultimately, California’s own high-speed rail project.

Brightline ran its five-train fleet carbon neutral throughout February 2020 and all of the company’s carbon emissions will be offset with renewable energy credits. In addition, its trains are fuelled by biodiesel and meet Tier-4 emissions standards, plus Brightline stations in Fort Lauderdale and West Palm Beach feature FPL SolarNow trees, structures that provide shade and harness solar power.

Brightline trains in the US are fuelled by biodiesel and meet Tier-4 emissions standards.

The UK: HS2 and Eurostar

Across the Atlantic, the High-Speed Rail Group is lobbying the government to decarbonise the UK’s rail system by 2040, and heralded the High Speed 2 (HS2) project as a “new carbon transport backbone for the UK".

Supporters argue that HS2 will reduce demand for air travel, road freight and car journeys by linking northern England with the Midlands, London and High Speed 1 (HS1) to the Channel tunnel and continental Europe.

The Guardian reports on claims by HS2 that the service can achieve 8g of carbon emissions per person per km compared with 67g of emissions from the same journey by car and 170g by plane.

However, the report goes on to argue that the UK Government’s own calculations for HS2 suggest the route’s carbon emissions could exceed potential savings; that overall construction and operation will result in 1.49 million tonnes of CO2 equivalent at a time when emissions need to be falling rapidly to reach net-zero; and that the UK Department for Transport suggests the modal shift to HS2 from driving and flying will be negligible.

Meanwhile, Eurostar claims it has reduced carbon emissions in the past eight years by 32%, and that a Eurostar journey from London to Paris emits 90% less greenhouse gas than the equivalent short-haul flight and less carbon per passenger than a journey from central London to Heathrow.

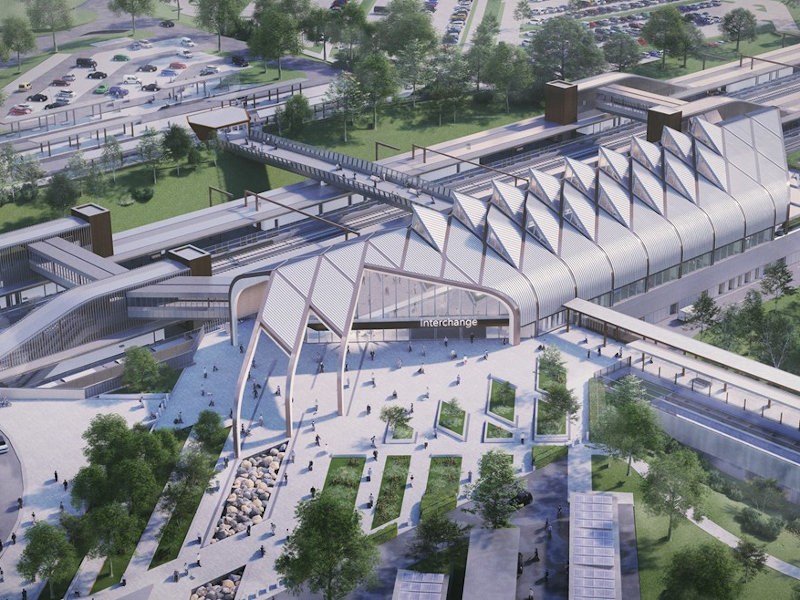

The HS2 interchange Station east of Birmingham.

France and Spain: Euro vision

In France, the state-owned rail operator SNCF has introduced a raft of measures aimed at boosting energy efficiency and slashing emissions. Global Railway Review reports that the Renfe-SNCF in Cooperation high-speed service has allowed for a saving of half a million tonnes of CO2 since 2013.

When taking into account domestic travellers using Renfe-SNCF in Cooperation’s services in France and Spain, the figures increase to around one million tonnes of CO2 saved, a figure that corresponds to the average annual emissions from electrical consumption by a city with a population of 3.7 million.

The high-speed trains between Spain and France run on renewable electrical energy and have a low carbon footprint, with every 100km travelled enabling an emission reduction of around 15kg of CO2.

Speaking at the International Union of Railways’ (UIC) low-carbon mobility conference in Brussels in February 2020, UIC director-general François Davenne noted that, among other benefits, passenger rail overall requires less than one-tenth of the energy needed to move an individual by car or plane and that trains have a 30-year lifespan, minimising the need to invest in non-renewable resources.

Affordable, energy-efficient high-speed rail services offer an alternative to road travel.

Japan: bringing it all back home

In a 2019 case study published by Triodos Investment Management – which invests in companies that “actively contribute to a sustainable economy through their products, services and processes” – the firm explains the rationale behind its decision to invest in Central Japan Railway (JR Central).

JR Central generates 70% of its annual revenues from the Tokaido Shinkansen high-speed train line, which transports 452,000 passengers daily (165 million per annum) between Tokyo and Osaka.

Triodos claims that, compared with an aeroplane on the same route, the line uses 88% less energy and produces 92% fewer carbon emissions per seat, and that for distances of up to 1,000km, travelling by high-speed train is time and price-competitive with air travel. JR Central has also outlined plans to reduce its energy consumption by 25% by the end of 2030 compared with 1995 levels.

A Japanese Shinkansen high-speed bullet train at JR Osaka station. Image: Icosha | Shutterstock