Ticketing

Is the ‘death of the commute’ forcing a ticketing rethink?

Traditional rail tickets are generally structured around the average workday, with peak or off-peak prices shaped around rush hour and weekly season tickets. Yet with many now working from home, should fares and tickets change to reflect new commuter patterns? Adele Berti finds out.

Adele Berti: Taxing the railways is counter-productive and a smack in the face for sustainability

It’s supposed to be a fairly straightforward equation: travelling via rail is less polluting, so more people using it equals substantial decreases in the UK’s carbon output. And yet, as passengers and commuters prepare to return to their offices after long months of lockdown and the summer holidays, rail fares remain high and are expected to increase by 1.6% in January, based on July’s annual Retail Price Index.

Meanwhile, far bigger polluters in the aviation industry still get away with relatively low air passenger duty, the absence of value-added tax charges (which the railways don’t pay either) for international flight tickets in the EU, and a tax fuel exemption. All the while, rail transport is responsible for up to 85% less carbon per passenger kilometre than several other forms of transport, according to research published by the Campaign for Better Transport.

Sustainability championssuch as Germany, Austria and Luxembourg have acknowledged this disparity and are pioneering new initiatives to make rail travel more convenient at aviation’s expense. For example, last year Germany approved a 10% cut in long-distance rail fares for the first time in 17 years. The Austrian Government has promised an expansion of its rail network and plans to increase taxes on flights. Lastly, Luxembourg is making all public transport free.

On

an average weekday, London Waterloo station, the largest and busiest railway hub in the UK, used to welcome 125,000 journeys, equalling some 94.2 million journeys a year. During the peak of the UK’s first lockdown between March and April, this figure dropped by a staggering 95% as more and more people shifted to working from home to minimise Covid-19 transmission.

Months later, with the prospect of returning to those levels looking unlikely in the short term, members of the UK rail industry are faced with the need to reform the fares system with a less commuter-centric vision.

Their idea – which is being shared by many other rail networks around the world – is that commuter habits will radically change as more and more people get used to working from home to limit the spread of the virus.

This is forcing the UK Government to shake up rail fares and shift towards a more flexible set of tariff options that could come into effect once lockdowns are over or if a vaccine is commercialised. How would this transition take place, and what role will commuters play in future fares plans?

Brightline senior vice president, corporate affairs, Ben Porritt

Aerial view of the derailment. Image: UK Government

Accelerating a change that was already there

The pandemic has severely disrupted most commuter habits, but according to Paul Tuohy, chief executive of UK transport non-profit group Campaign for Better Transport, signs of a shift in passenger working behaviours were there long before Covid-19.

“Commuter tickets have been out of step with modern working patterns for many years,” he says, citing research from the Office of National Statistics. “The number of people working part time and flexibly was rising even before the pandemic and with millions of people set to continue working from home for at least part of the week for the foreseeable future, if not permanently, the need for a more flexible approach to commuter tickets has only increased.”

But this transition would have taken considerably longer had it not been for the pandemic, which has brought rail services to a near halt worldwide, severely impacting revenues. Figures from ITV show that rail usage plummeted to 23% of pre-Covid-19 levels between March and August, while research from the Office for Budget Responsibility revealed a drop in UK rail journeys of 51 million during the fourth quarter of 2019-20.

Commuter tickets have been out of step with modern working patterns for many years

“The Covid-19 crisis has had a seismic effect on commuter habits, with the number of rail journeys falling to its lowest since the mid-nineteenth century” he comments. “With many workers furloughed, working from home or taking to their cars, the impact on ticket sales - and therefore on the ability of the train operators to continue providing a service - has been so disastrous that the government has had to introduce emergency funding to keep trains running.”

This view is shared by Andy Wakeford, head of fares at rail operators umbrella organisation the Rail Delivery Group (RDG). He says that Covid-19 has catalysed a change in passenger habits, similar to how retail trends are shifting from the high street marketplace to ecommerce.

“People will need to travel and are going to want to visit places, so that [trend will] come back,” he adds. “But with other things like commuting it is very clear that people’s move away from five-days-a-week in the office has been dramatically accelerated, and we need to accommodate, recognise and adapt to that.”

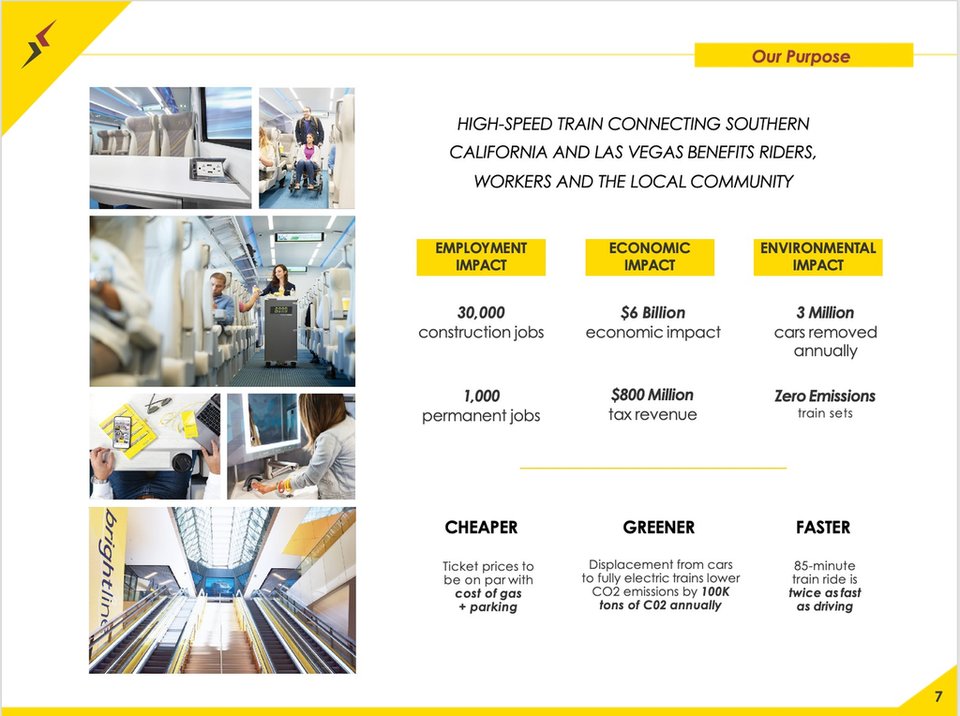

By offering an eco-friendly, efficient service, Brightline hopes to accelerate the modal shift from road and short-haul air travel to rail.

How can train operators support new passenger habits?

“If the way that a good chunk of your market wants to travel has changed, it makes sense to offer that new market a product that fits it,” argues Mike Hewitson, head of policy at transport passenger watchdog Transport Focus. “By that, I mean that people who buy a weekly season ticket won't want to pay for a weekly ticket just to use three days, so [we support] more flexibility in ticketing.”

Transport Focus has long been campaigning for the introduction of part-time season tickets, as well as discount ‘carnet’ bundles and other ‘mix-and-match’ solutions that would give travellers greater freedom of choice. Some of these recommendations are currently being considered by the government, which is working with the RDG on new types of fares for a post-Covid world.

As Wakefield explains, flexible season tickets make for a compelling case. “Flexible tickets are not just good for rail but also for the economy as the government recognises that you need to get people travelling back into offices," he says. "If that's not going to be full time and five days a week, well that's probably good for people's quality of life but there's a difference between having to come in every day and being stuck at home all the time.”

Flexible tickets are not just good for rail but also for the economy

“One of the things that has been discussed is a flexible package type of ticket where you buy a certain number of journeys that has to be used within a certain length of time, but you have the freedom to choose when to use them.”

Campaign for Better Transport is a long-term supporter of their adoption, arguing they offer advantageous revenue opportunities. “Part-time season tickets would encourage people currently not travelling to return to the trains, thereby increasing revenue,” says Tuohy. “There's a real danger that if season tickets for people who want to commute part-time aren't introduced soon, passengers will abandon trains altogether and take to their cars, with disastrous consequences for traffic levels, air pollution and the environment.”

But this model will have to be balanced out with many train operators’ increasingly strong stance on train bookings. As Transport Focus’s Hewitson mentions, before the pandemic it was easier to hop on a train – even long-distance ones – without booking a ticket in advance.

“Some of the long-distance operators are moving more towards mandatory reservations, while before you would be able to buy a type of off-peak ticket that allowed you to turn up and jump on,” he says. “So, it will be interesting to see whether long-distance railways will continue to require a reservation.”

No more peak and off-peak train tickets?

Among the most obvious consequences of the pandemic is the need to re-evaluate the concept of peak and off-peak fares. This is currently being considered in Japan, where train operator JREast is studying the feasibility of adjusting its fare system based on traffic volumes, rewarding passengers who avoid peak hours.

As for the UK, reforming the entire fares system is something that the RDG, Transport Focus and Campaign for Better Transport have all been advocating for years, putting the stress on-peak and off-peak tickets. While changes were expected to come from the long-awaited Williams Rail Review, this was pushed back due to Covid-19.

Yet even in the absence of the review, the past year has shown a change in commuting habits that fare policymakers will need to consider in the future. “It's not for us to decide when peak or off-peak is as that's what customers decide,” says Wakefield. “What we're saying is that we want more flexible ticketing that could work more in harmony with that.”

It does seem a really opportune time to come back with a new fare structure

Key to achieving this will be, he stresses, a “proper reform of the fares system” that will support the introduction of digital, smart and simpler tickets to better suit people’s lifestyles. “We need simple straightforward options that clearly delineate what is the best deal, rather than outlining 400 different ticket offers and have you work out which one you think might be right,” he adds.

Similar sentiments are expressed by both Hewitson at Transport Focus and Tuohy at Campaign for Better Transport. “If we are coming back with a brand-new railway it does seem a really opportune time to come back with a new fare structure as well,” says the former. “There are certain things that we would really like to see in any new fare structure, one of which is a shift towards single-leg pricing.”

“A complete reform of fares, fare structures and ticketing is long overdue,” adds Tuohy who has also been lobbying against the expected increase in rail fares by 1.6% from January. “We think there should be a rapid move to simplified fare structures, account-based ticketing (like London’s Oyster system) and an integrated multi-modal approach with tickets transferable between trains and buses.”

Whatever the changes will be, all three stress they won’t be introduced all at the same time in the aftermath of lockdowns, but rather through gradual developments that can be modified and updated depending on traffic levels, new commuter habits and more. “We're very keen that there is change that people can see quickly,” concludes Wakefield. “This may not be the end product or the finished product but it's all part of it.”